Could a machine learn the structure of the solar system?

in Blog

There is a lot of interest right now in whether or not AI and machine-learning methods can help scientists develop new scientific insight. In this blog post, I will illustrate how universality, which is one of the major advantages of deep-learning models, is also a detriment when it comes to knowledge discovery.

Suppose that we were to provide a machine-learning algorithm with all the planetary motion data from Tycho Brahe. As you may know, Tycho Brahe’s careful measurement of planetary data played a central role in the development of Kepler’s laws, which in turn played a central role in Newton’s theory of gravitation. The theory of gravitation gave a compelling physical mechanism that rationalized Copernicus’ heliocentric model, versus the prevailing geocentric model.

The heliocentric model is so obviously engrained in our intuition that it might seem obvious that a computer would pick the heliocentric model. But you might be surprised to learn that both the heliocentric and the geocentric model can describe planetary motion fairly well.

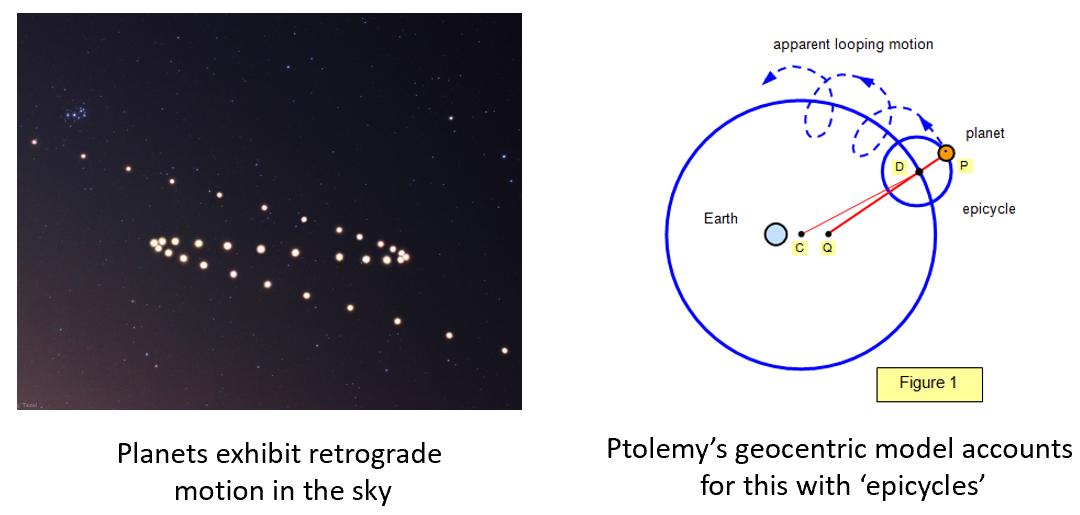

Perhaps the most challenging phenomena to describe within the Geocentric model is the observation of Retrograde Motion, where planets backtrack briefly during their trajectory across the sky. Remember that Ptolemy, who came up with the mathematical description of a geocentric universe, was a smart guy. His geocentric model can accurately describe planetary motion because it operates based on a theory of epicycles. In the epicycle description, the planets do not just move on circles, but actually they move on circles around circles. The first circle is also not centered at Earth, but is slightly off centered. If you use epicycles, we can accurately predict planetary trajectories for several hundred years! In fact, mechanical projectors in old planetariums operate using the geocentric description of the solar system.

The reason epicycles work well is because they are a Fourier series, which can approximate any smooth function. In essence, Ptolemy’s geocentric model is essentially a two-term Fourier series. If we add more terms to the Fourier series, we can describe any smooth function – for example, here is another epicycle for my new institution, the University of Michigan:

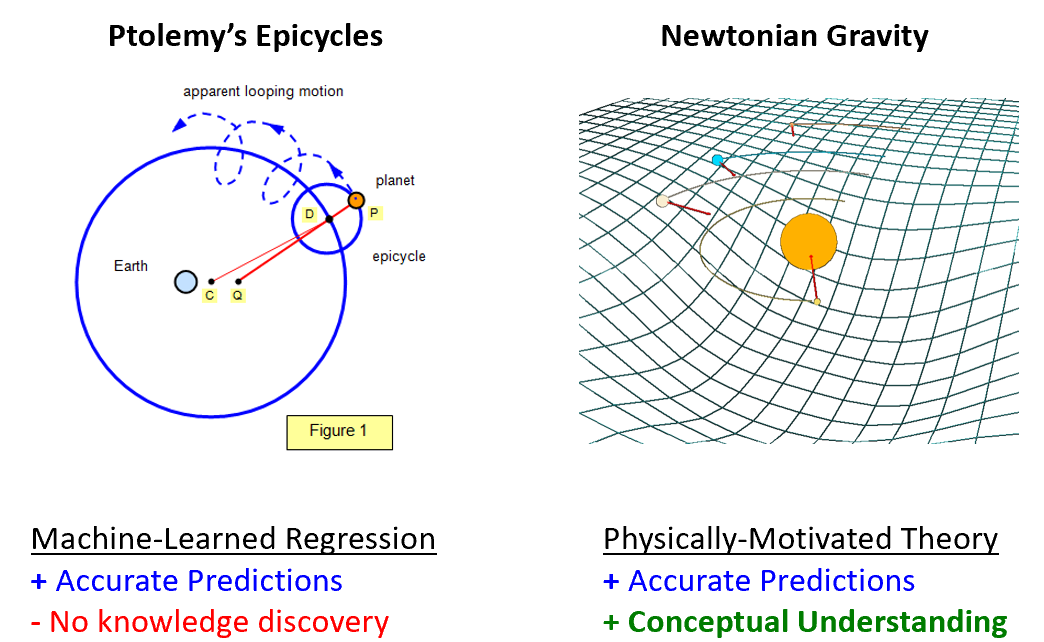

From a trajectory prediction perspective, the heliocentric model and the geocentric model provide similar value. So why does a scientist benefit from the heliocentric model? The heliocentric model is a structural form that gives rise to the physical mechanism of gravity. The mechanism of gravity provides a deep conceptual foundation for us not only to interpret planetary motion, but also apple-earth interactions (a la Newton). It is these deep, transferrable conceptual frameworks that form the intuition which scientists value so much.

Like Epicycles, many of the powerful tools that are driving the AI revolution, such as deep-learning / neural networks, are also universal function approximators. I have no doubt that a neural network could also predict planetary trajectories with high fidelity. The problem is that, just like the case of epicycles, we are getting the ‘right answer’ for the ‘wrong reason’. In other words, while a machine-learned regression/classification model can provide accurate predictions, like the Epicycles, it is challenging to derive any physical insight.

Let me conclude with one more example that is closer to chemistry and materials science.

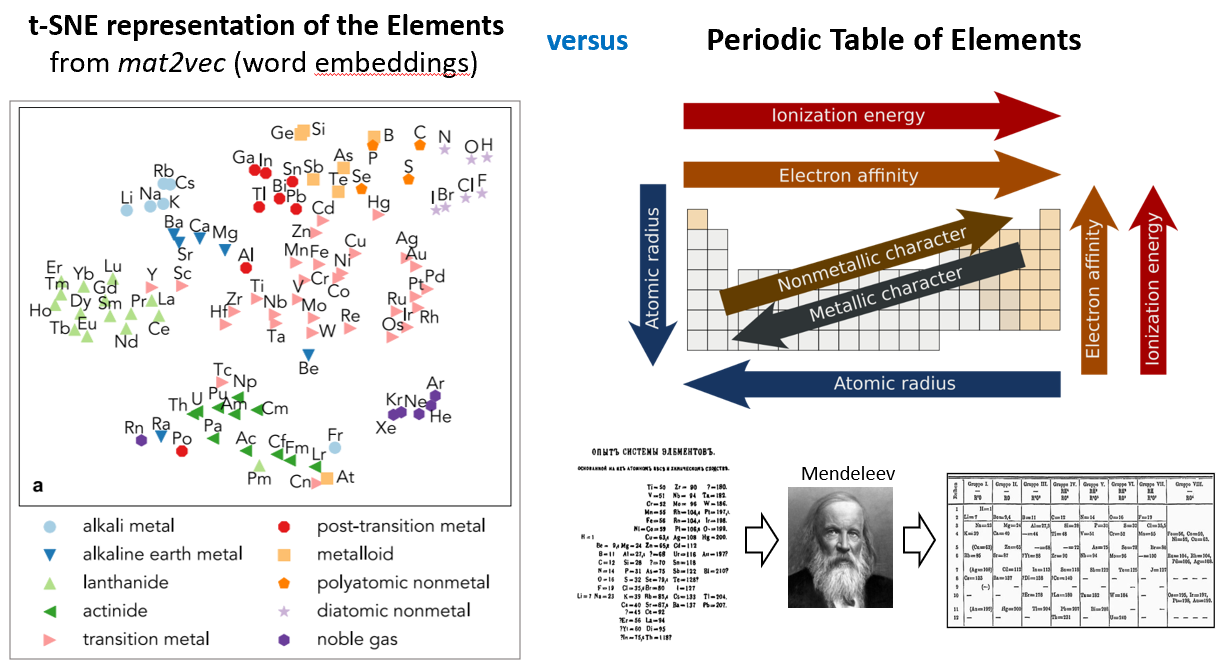

Here is a t-SNE representation of the elements, constructed from Word Embeddings of the Scientific Literature (Tshitoyan et al., Nature 2019). Here, a Word2Vec model is fed millions of abstracts from the scientific literature, which finds latent representations of the words from the text.

Let me start off by saying that this t-SNE representation is actually pretty spectacular. It is incredible that a computer can construct, just from word embeddings, a representation that actually does quite well in clustering the elements in sensible ways.

My question though is, if we did not know the Periodic table, in other words, if there were no colorful markers that distinguished the elements into existing classifications, and we were just presented with black dots for each data point, would we be able to tease out the structural form of the elements from this t-SNE plot? My guess is no. And to me, this is because the x- and y- axes in a t-SNE figure do not have any meaningful interpretation. Euclidean distances in this figure also do not have a real physical significance. Our appreciation of the clustering is post-hoc; we only appreciate that the t-SNE figure captures our existing intuition regarding the elements.

In contrast, let’s discuss Mendeleev’s Periodic Table. The Periodic Table is actually a very unusual and unique structural representation. It is not a scatterplot, it is not a clustered dendrogram, nor is it some ranked list.

When Mendeleev first created the Periodic Table, the organization was very phenomenological. Mendeleev started with the ansatz of Periodicity (based on the 4 suits in playing cards!), and it was inspired by this structural form that the first periodic table was made. Of course as time proceeded, the periodic table gained a more precise and also peculiar shape; the first row has two elements, the next two rows have eight, the next two rows have eighteen elements; and the next two rows have 32 elements.

As we today know, the structural form of the Periodic Table derives from the underlying s,p,d,f nature of the quantum-mechanical atomic orbitals. Not only did this heuristic representation of the Periodic Table accurately reflect underlying physics, this structural representation further led to the prediction of missing elements, which were later confirmed.

Because the Periodic Table reflects the underlying quantum mechanical structure of elements, it also provides tremendous utility in interpreting chemistry. As any first year chemistry student knows, the structural form of the Periodic Table can be navigated to make arguments about electronegativity, atomic radius, metallic/ionic/covalent character, etc. This is the representation that produces broad scientific value.

Much like the heliocentric structure of the solar system, and the periodic table, we interpret our world and universe from conceptual models. Many of these conceptual models have unusual structural form, and as far as I’m aware, this structural representation is not something that could pop out of any existing Machine-Learning package. From an engineering perspective, perhaps all we need is a good prediction. But referring back to the Epicycle/Geocentric analogy, a prediction of planetary trajectory may have useful engineering value, but it does not lead to a conceptual understanding of gravity, which has great value for building physical intuition and insight.

In my opinion, the great challenge to us computational scientists will be to go beyond what is easy to obtain from machine-learning models, and be more deliberate about building models that capture the true structural form of Nature’s representations.

One last statement; there may not necessarily be a ground-truth in a structural representation. What makes a good representation? I think that it is just the utility that it provides a scientist. The greater the utility, the better the representation. This is why we must distinguish any big-data problem into two parts, a data exploration phase, where we seek to understand and interpret our data. Then the next stage, which can be even more difficult than the exploration stage, is to find compelling visualizations that communicate our learned intuition in informative and pedagogical ways. In my opinion, this will be the true challenge for the data-driven scientist.

For further reading on structural forms, here is a beautiful and very inspiring PNAS paper titled, The Discovery of Structural Form.

EDITED: 2/7/2020

It’s remarkable how independent minds can often converge on the same general concepts. I recently found that this topic was specifically addressed in a PRL paper, published just last month, January 8th, 2020. (Note that my blog was written on 12/4/2019!)

The paper is titled, “Discovering Physical Concepts with Neural Networks”

I have to say that I am a little bit disappointed with the section actually addressing the heliocentric model. The conclusion was that by feeding the earth-observed (geocentric) trajectories of the Sun and Mars in the sky, the latent representation of the planetary trajectory in the neural net was heliocentric in nature.

Something I tried to stress in this blog is that actually, a heliocentric model is not intrinsically better than a geocentric model, at least not from a trajectory prediction perspective. One might prefer a heliocentric description because it is simpler, but this is more of an “Occam’s Razor” assessment, where a simpler model is preferrable to a more complex model. But it doesn’t mean that the geocentric representation is intrinsically bad. Furthermore, is a heliocentric model really the purest representation of the planet trajectory? What about a galaxy-centric model? Then maybe the best representation looks like this:

Maybe all of this representation-discussion is a red-herring anyway, because at the end of the day, what a physicist really desires is a unifying physical principle, like Gravity. Gravity is consistent with the geocentric, heliocentric, and galaxy-centric models; and has its own wonderful set of implications and consequences, such as Kepler’s laws, etc. I still do not see any ML approach that can produce a concept like Gravity. But the field is moving fast and I would not be surprised to see that solved in the upcoming year or two.

What would excite me next is to imagine the wonderful things we could learn from applying these models to chemistry and materials science.

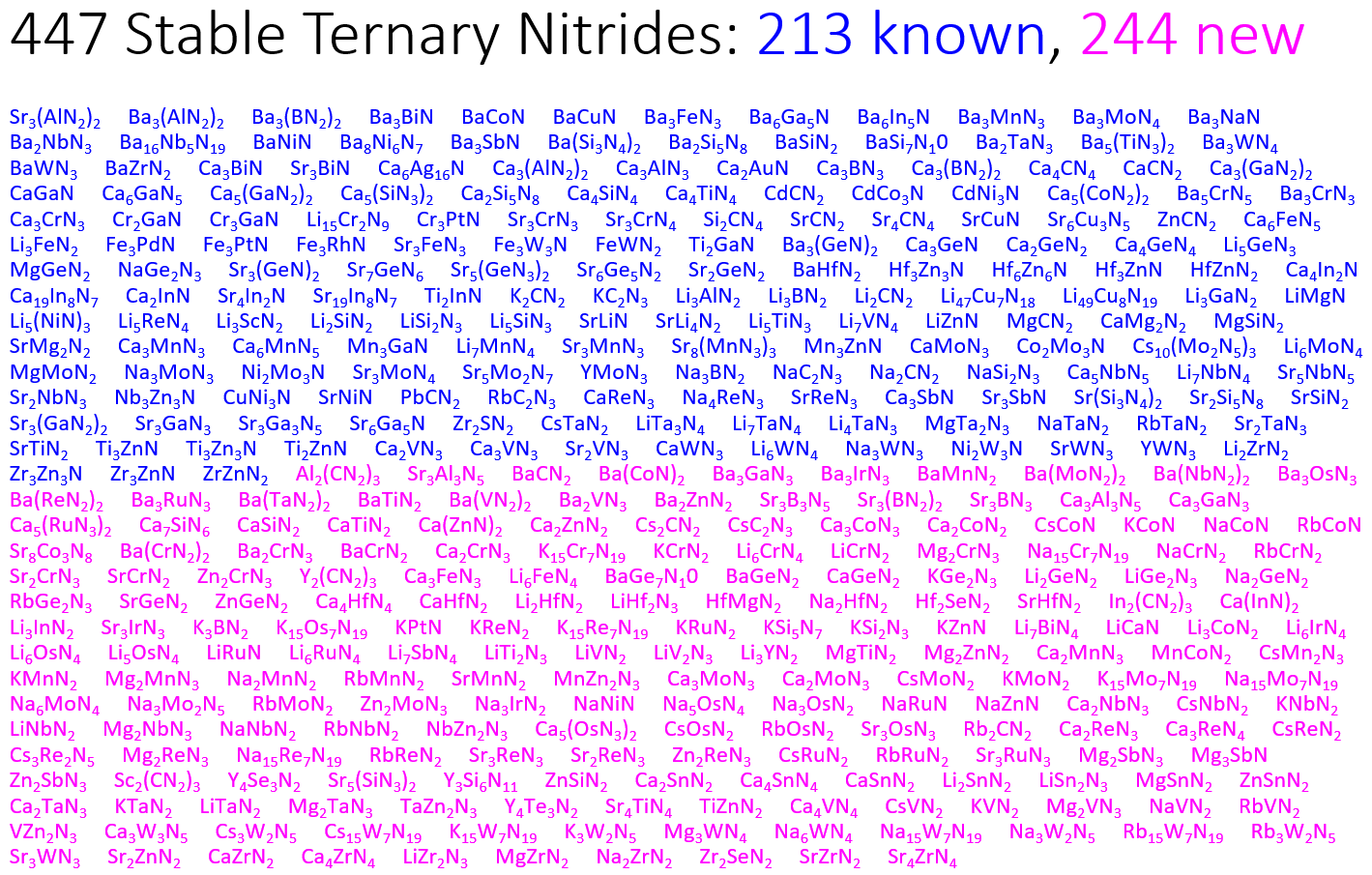

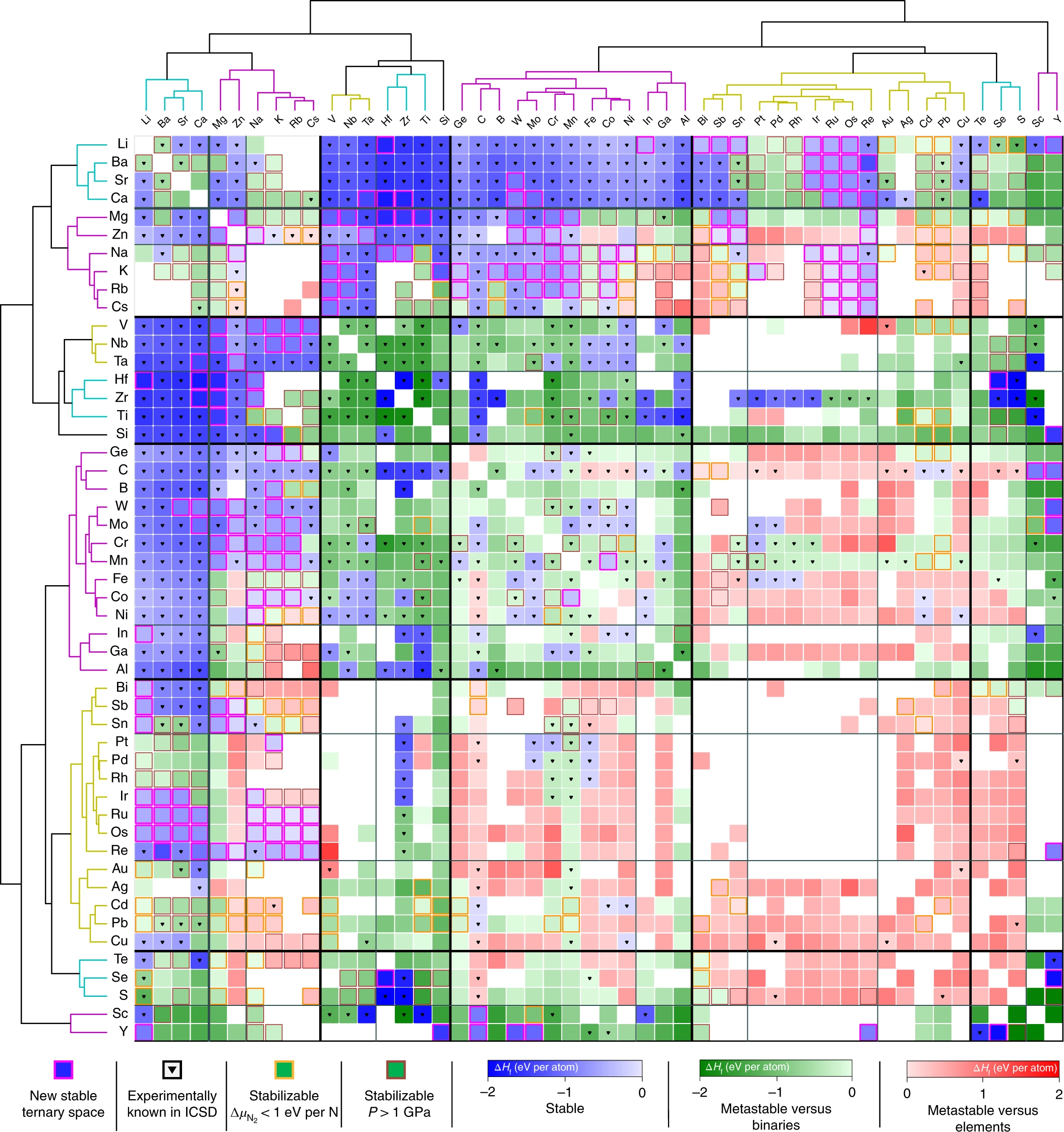

Previously known nitrides are shown in blue. Our predicted stable nitrides are highlighted magenta.

Previously known nitrides are shown in blue. Our predicted stable nitrides are highlighted magenta. A Map of the Inorganic Ternary Metal Nitrides

A Map of the Inorganic Ternary Metal Nitrides