Mapping Uncharted Chemical Spaces

in Blog

There is something deeply human about exploration. Within each of us, there is a great curiosity to venture into the unknown—to discover something new. There is a disappointing quote about our generation: “We are the middle children of history. Born too late to explore earth, born too early to explore the stars.” But there is still a new frontier being explored today—chemical space.

Chemical space is not really a physical place, but discovery of new compounds is not so different than discovery of a new island or continent. When you mix different chemicals together, sometimes they will react to form new compounds, and sometimes they do not. Discovery of new compounds can be wonderful by itself; but it can also be very practical. Newly discovered materials can be used to build safer cars, lighter airplanes, faster computers and longer-lasting phones.

Which elements will react together to form a new compound? Actually, it is not so easy to say. We have some ideas and principles to guide us, but they’re not perfect. For this reason, there is a lot of risk involved in chemical exploration.

Exploratory synthesis is especially risky when the target compounds are difficult to make. Nitrides are one such class of materials. Even though the atmosphere is 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, nearly all minerals (rocks) are oxides. Nitride minerals are exceedingly rare. Chemically speaking, O2 is double-bonded and N2 is triple-bonded, meaning that most metals would rather react with oxygen than nitrogen. Nitrides can be synthesized under special laboratory conditions, but even then, many metals will not react with nitrogen, and so it is risky to try different compositions randomly. However, many of the successfully synthesized nitrides are technologically important—Gallium Nitride in particular is a primary component in white-light LEDs, and its discovery was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014.

Four years ago, I joined the Center for Next Generation Materials by Design, a large team-science research center, where one of the goals was to discover new nitride materials. Using modern methods of computational materials science and machine-learning, we computed the stability of thousands of new candidate nitride materials. By evaluating the stability of these hypothetical nitride materials computationally, we could inform experimentalists about which nitride compositions were promising, and which were risky, which helps to focus their synthesis efforts.

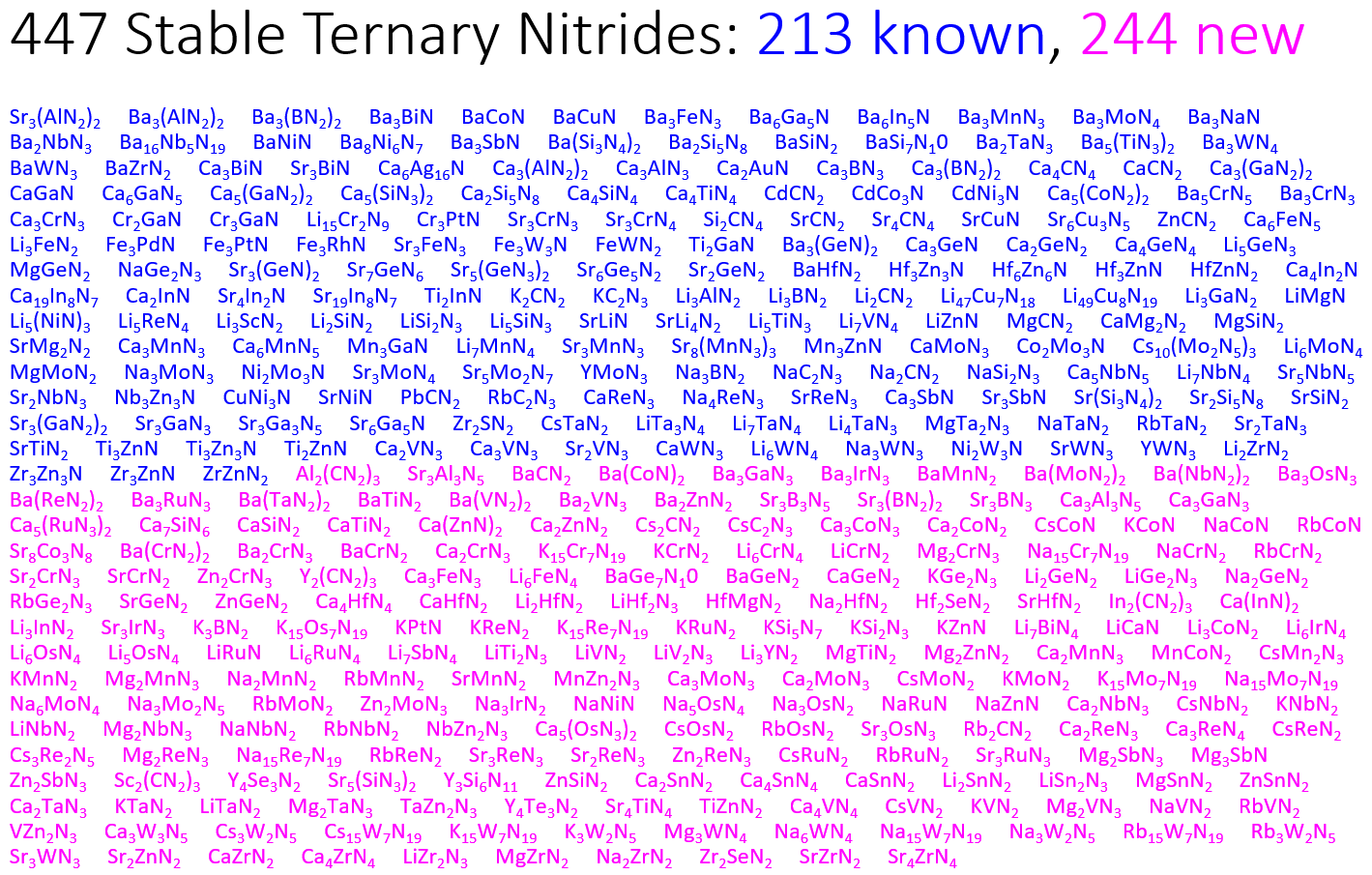

Our search resulted in the prediction of 244 new stable nitride materials. Previously, there were only 203 known stable nitrides, meaning that our computational discovery efforts more than doubled the number of known stable nitrides!

A large list of stable compounds is very impressive to look at, but … it is actually not completely satisfying. Why do certain elements react favorably to form nitrides, whereas others do not? This is a deep, fundamental question that probes at the very heart of solid-state chemistry.

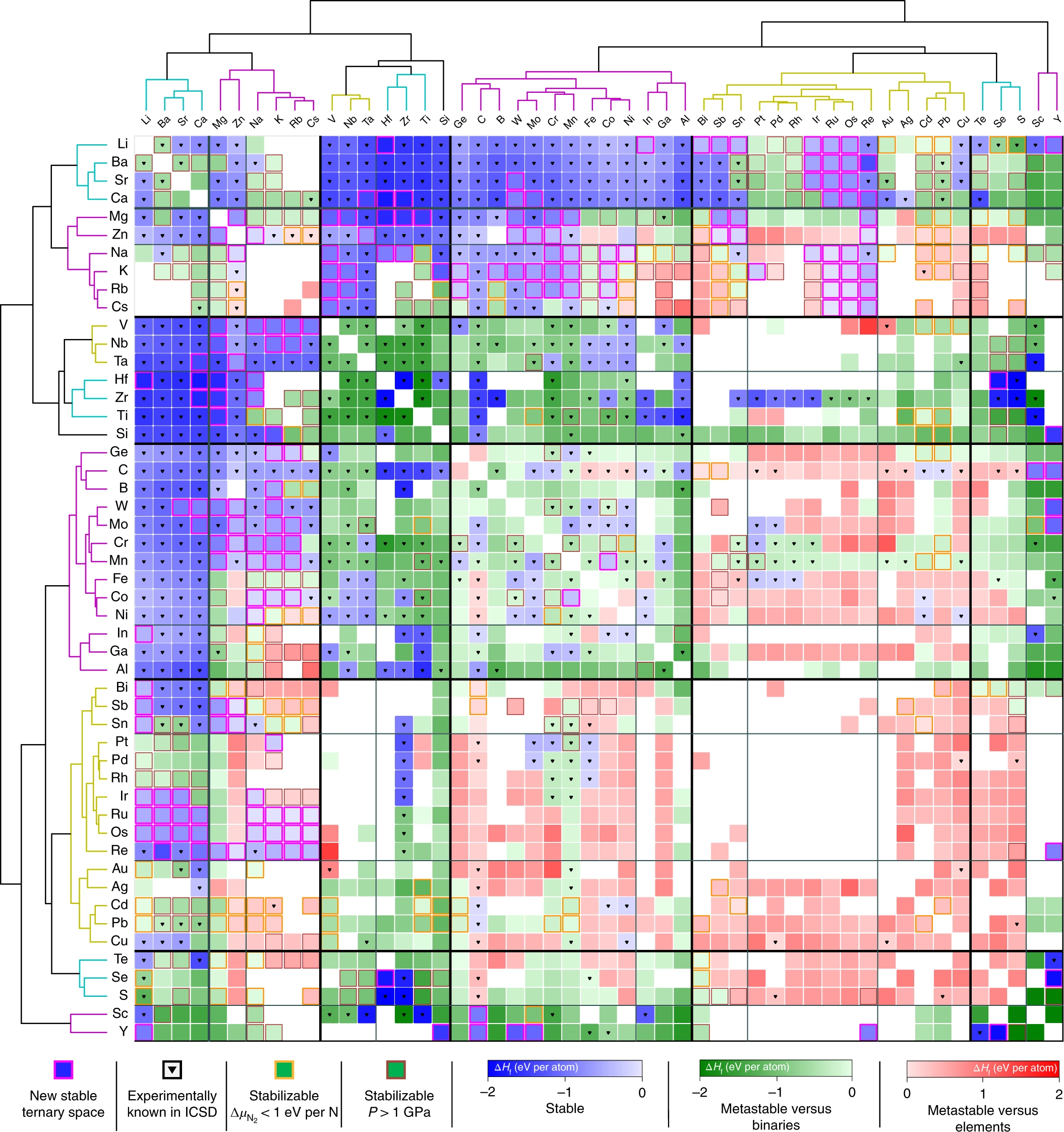

To reveal the chemical families in the ternary nitrides space, I used unsupervised machine-learning methods to cluster together which metals have a strong propensity to form ternary metal nitrides, and which do not. The result was a large nitrides stability map, which highlights regions of stability (blue), metastability (green), and instability (red).

A Map of the Inorganic Ternary Metal Nitrides

A Map of the Inorganic Ternary Metal Nitrides

You can interact with the map here, and see the phase diagram and stability information each ternary nitride system in great detail.

Just as ancient maps could be used to guide explorers to new lands, stability maps can be used to guide chemists in their exploratory synthesis of new compounds. Based on our predictions, our experimental colleagues at NREL successfully synthesized 7 new transition metal nitrides, which had never been made before. Surprisingly, these 7 new nitrides turned out to be semiconductors, which was fairly unexpected, as semiconducting nitrides usually do not contain transition metals. What can these new nitrides be used for? We’re still exploring that question, but we’re all very excited about where this can go.

What excites me the most is that we also developed new methods to explain the large-scale stability trends in the ternary nitrides. My collaborator, Aaron Holder, at the University of Colorado, Boulder, built new tools to extract the nature of chemical-bonding within these compounds, which we used to explore the metallic, ionic and covalent bonding in stable nitride materials. But perhaps this will be the topic of a later blog post.

In the meantime, please see the links to the map and the papers, and some external press releases of our work. It was a real pleasure to have collaborated with these talented and passionate scientists in the discovery of new nitride materials.

Interactive Ternary Nitrides Map

Nature Materials Article, A map of the inorganic ternary metal nitrides

Paper by Elisbetta Arca on the synthesis of our first predicted ternary nitride material, in the Zn-Mo-N space, which has remarkable band-gap tunability with the Zn/Mo ratio.

Paper by Elisbetta Arca on the synthesis of the first antimony-containing nitride semiconductor, Zn-Sb-N

Paper by Sage Bauers on the synthesis of several new Magnesium-based ternary metal nitride semiconductors, surprisingly, in the rocksalt crystal structure, in constrast to the traditional wurtzite III-N semiconductors.

Some early papers by Andriy Zakutayev and myself on how N2 can be chemically-activated to synthesize nitrogen-rich nitrides.

See also a blog post by Anubhav Jain that helped inspire these ideas.